1 数学的問題解決論の位置づけ

1.2 数学的問題解決論=問題解決能力形成論 2 問題解決過程論

2.2 合理的問題解決過程 2.3 問題解決過程 2.4 メタ認知過程 3 問題解決機制論

3.2 合理主義的発想としての"問題解決機制論" 3.3 情報処理システムの問題解決 3.4 "問題"と"心"の二元論 3.5 "問題"との対峙 3.6 問題の受容 3.7 自動機械の上の事態としての問題解決 3.8 問題解決の機制 3.9 問題空間の探索 3.10 ストラティジーの所有 3.11 スキーマ 3.12 ストラティジー発動の機制の説明不能 3.13 問題解決機制論の基底 3.14 "メタ認知" 4 問題解決能力論

4.1.2 "good problem-solver" の概念規定の目的 4.1.3 "good problem-solver" の概念規定の実際

4.2.2 "問題解決能力"措定の不能

5 問題解決能力形成機制論

5.2 問題解決能力形成の機制の説明不能 6 問題解決能力形成実践論

6.2 "ストラティジー指導"の発想経路 6.3 ストラティジー形成の実践における採用仮説 6.4 内容フリーの機制の説明不能との関連 6.5 "ストラティジー指導"の実際 6.6 メタ認知の形成 1 数学的問題解決論の位置づけ 1.1 認知科学内問題解決論との連続性 数学的問題解決論は,問題解決能力形成論として(§1.2),認知科学内問題解決論=問題解決機制論に連なる。 この解釈を支持するものとして,F.K.Lester,Jr. の認識を以下に示す:

(註1) Dewey の"reflective thinking"モデル (Dewey,1933,pp.113,114):

2. intellectualization, 3. hypothesizing, 4. reasoning, 5. testing the hypothesis by action. (註2) Polya の"problem solving"モデル (Polya,1957):

2. devising a plan, 3. carrying out the plan, and 4. looking back. (註3) §§3.5, 3.6 で引用されている Newell and Simon と Lester の表現の類似性を見よ。 1.2 数学的問題解決論=問題解決能力形成論 数学的問題解決論は,問題解決機制論の制限──問題一般を数学の問題に限定するもの──ではない。それは徹頭徹尾,問題解決能力形成論(註1)である。 そのようなものとして,数学的問題解決論を,

(2) 問題解決能力形成機制論 (3) 問題解決能力形成実践論(指導論)

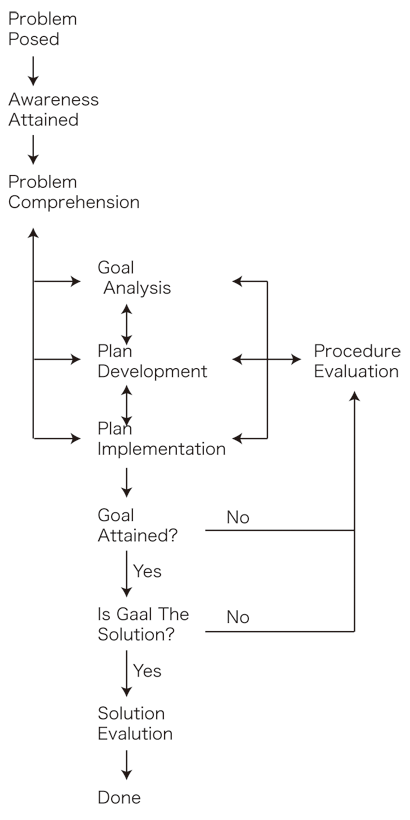

(1.2) "問題解決能力"の措定 (1.3) 問題解決能力機制論──問題解決能力の機制についての論考 (註1)"能力育成"ではなく"能力形成"の言い回しを用いる。"能力形成"の言い回しは日常語的に不自然であるが,合理主義的オリエンテーション下の"能力"解釈では,"能力育成"ではなく正に"能力形成"になる。 (註2) コンピュータ・シミュレーションをつねに念頭においている認知科学内問題解決論では,問題能力を全く内容フリーなものとして直接主題化するということはない。そこで本論では,問題解決能力の主題化を,問題解決能力形成の主題化と併せて,数学的問題解決論に帰属させ,同時に数学的問題解決論を問題解決能力形成論として特徴づける。 2 問題解決過程論 本節では,問題解決過程に対する合理主義的理解の形態を述べる。 2.1 問題解決過程論の記述レベル ここで記述されるのは,問題解決過程として何が起こるかであり,それがいかにして(即ち,どのような機制によって)実現するかではない。──後者は問題解決機制論(§3)になる。 2.2 合理的問題解決過程 合理主義的オリエンテーション下での問題解決過程の理解は,それが合理的な過程だということである")。 (註) 即ち, "1 状況を,明確に定義された属性 property をもった,明確な対象 object によって記述する。 2 対象や属性で記述した状況に適用される一般的ルールを見出す。 3 問題となっている状況に,ルールを論理的に適用して,何をすべきかという結論を導く。 対象や属性の体系的な「表象」を状況にどのように対応づけるか,一般的ルールをどのように知るかというのは,決して簡単な話ではない。しかし合理主義的伝統にあっては,体系的ルールを定式化しさえすれば結論を論理的に導けるという面が強調され,これらの問題は後回しにされている。" (Winograd and Flores,1986,pp.22) 2.3 問題解決過程 問題解決過程は,以下のような図式で理解される:

(Lester,1978,p.82) 2.4 メタ認知過程 問題解決過程にメタ認知過程を含める考え方が,ここしばらくの間,一部に定着してきている")。メタ認知論は,(メタ認知の存在身分の言及が必要になる)問題解決機制論においてほころびを呈するが,(存在身分の言及を無しで済ませることのできる)問題解決過程論においては,一応安全な論考でいられる。 例えば,つぎのような言い方をしている間は大丈夫である: In any kind of cognitive transaction with the human or nonhuman environment, a variety of information processing activities may go on. Metacognition refers, among otherthings, to the active monitoring and consequent regulation and orchestration of these processes in relation to the cognitive objects or data on which they bear, usually in the service of some concrete goal or objective. (Flavell,1976,p.232) Goal analysis can be viewed as an attempt to reformulate the problem so that familiar strategies and techniques can be used. (Lester,1978,p.80) (註) メタ認知を発想する理由は,つぎのようである: Procedures and solution evaluation may be viewed as a process of seeking answers to certain questions as the problem solver works on a problem. (Lester,1978,p.81) 3 問題解決機制論 3.1 問題解決機制論の概要 (1) 問題解決機制論は,合理主義的オリエンテーション下の論考である。特に,問題解決は"情報処理システムの問題解決"へと理想化される。

(2) 問題解決機制論は,"問題"(外)と"心"(内)の二元論という体裁をとる。 (3) 問題の受容:

(3.2) 二様の"問題"の措定に応じて,二種類の"意味"概念を導入しなければならなくなる。即ち,字義的意味と文脈依存的意味である。 (3.2) "問題の受容"の以上の論点は,合理主義的オリエンテーションの一般的論点の適用に他ならない。 (4) 問題空間:

(4.2) 《問題解決は人に依存する》という事実は,自動機械の

(2) 初期状態 (5) 問題解決:

(5.2) 即ち,《ストラティジーの選択とそれの適用》により,所与の問題に対応する表象が次第に解に対応する表象に変化していくという図式である。 (5.3) ストラティジーの選択が問題空間の探索として捉えられ,問題解決が"問題空間の探索"として表現される。 (5.4) この探索は,ストラティジーが適用される表象をノードとし,ストラティジーを選択肢とする木 tree で表現される。 (6) ストラティジーの所有:

(6.2) "ストラティジーの所有"の概念は,"ストラティジーの所有形態","ストラティジーの発動形態"の問題をもたらす。 (6.3) 合理主義的なオリエンテーションに従うならば,ストラティジーは内的な命題として所有され,そして命題的態度 propositional attitude として発動していることになる。 (7) 問題解決機制論のほころび──ストラティジー発動の機制の問題:

(7.2) "メタ認知"の概念が,ストラティジーに対する"driving force"として導入されることがある。しかしこれは,解決をもたらすものにはならない。実際,メタ認知の実体はメタ表象であるとされるので,"メタ認知"の導入は新たなストラティジーの導入に他ならず,したがってそれは単に"ストラティジー発動"の無限後退の問題をもたらすだけである。 (8) 問題解決機制論の基底(ブラックボックス):

(8.2) 即ち,ストラティジー発動は,自動機械のプログラムとして理解されねばならない。 (8.3) "プログラム"の概念を問題解決主体に移すならば,それは"傾向性"になる。結局,問題解決論は,その根底に"傾向性"というブラックボックスを用意しなければならない。この事態は,"説明はどこかで終わらなければならない"という Wittgenstein のことばと符合する。 3.2 合理主義的発想としての"問題解決機制論" "問題解決機制論"の発想は,問題解決一般の法則定立的説明を試みようという発想であり,それは合理主義的発想である。 この発想が(自然なものというよりは,むしろ)独特なものであることは,例えば,つぎの"家族的類似性"の発想(Wittgenstein)と対比することでも明らかになる:

"問題解決機制論"の発想の特殊性をこのような形で一先ず認識した上で,以下,問題解決機制論の分析を試みる。 3.3 情報処理システムの問題解決 問題解決に対する"問題空間の上の探索"の解釈の元には,問題解決主体に対する"情報処理システム"の解釈がある。 人間知能に対する情報処理システムの解釈はコンピュータの作成を導いたが,つぎには,この解釈がコンピュータ・アナロジーの形で強化されることになる。 コンピュータ・アナロジーからさらに,"コンピュータ・シミュレーション"の発想が出てくる。即ち,"モデルをコンピュータ・プログラムに書き直し,このプログラムでコンピュータが所期の動作をするかどうかを見る。所期の動作をすれば,モデルは妥当と見なされる。 コンピュータ・シミュレーションにおいてコンピュータは"尺度"として機能させられていることになる。(これは"シミュレーション"の意味にしたがう。)このように,コンピュータ・アナロジーからコンピュータ・シミュレーションへの移行の意味は,"主客の転倒"である。 3.4 "問題"と"心"の二元論 問題解決機制論は,"問題"(外)と"心"(内)の二元論の体裁をとる。即ち,以下のようになる。 問題は最初,物質世界内存在として心に対峙する。心はこれを内的表象化し,自らの部分にする。問題解決は,この心が一定の状態へ解発していく過程である。 このときの合理主義的オリエンテーションは,特に表象主義である。 3.5 "問題"との対峙 問題との対峙──即ち,"心"による"問題"の対象化──という事態は,つぎのように捉えられる:

A problem is a task for which: 1. the individual or group confronting it wants or needs to find a solution; 2. there is not a readily accessible procedure that guarantees or completely determines the solution; and 3. the individual or group must make an attempt to find a solution.(Lester,1983,pp.231,232) A problem is a situation in which an individual or group is called upon to perform a task for which there is no readily accessible algorithm which determines completely the method of solution. ... ... any reference to a problem or problem solving refers to a situation in which previous experiences, knowledge, and intuition must be coordinated in an effort to determine an outcome of that situation for which a proceddure for determining the outcome is not known.(Lester,1978,p.54) ここでは, (a) "処理手続き" を既に持っているのに,それにアクセスできない ということが専ら強調されている。実際には,問題が(直ちには)解けない("問題"である)理由は,(a) の他に (b) "処理手続き" が持たれていない でもあり得る。 しかし,問題解決論のオリエンテーションでは,(b) の場合も (a) の場合と同様に問題解決に入っていくとされる。したがって,(b) は実際上 (a) の特殊と見なせるわけであり,(a) のみが強調されていることを片手落ちと見なす必要はない"1)。 ここでの最も重要な論点は,"どんな行動をすべきかが直ちにはわからない"ということの機制である。 実際,この論点は,問題解決機制論において本質的である。何故なら,"解決不能"に対する"解決の潜在力はあるがそれの発揮の仕方がわかっていない"という解釈(理解の仕方)は,極めて独特だからである。この解釈は,"問題は〈処理手続き〉によって解かれる"という解釈の裏返しである。その発想の元には,

しかし問題解決機制論の現状は,"どんな行動をすべきかが直ちにはわからない"ということの機制がブラックボックスにされている,というものである"2)。そしてこれが,問題解決機制論が踏み出す最初の一歩である。 (註1) (b) は,問題解決能力形成論において論点になる。──実際,問題解決能力形成論は,"解釈の潜在力もない"状態から"解決の潜在力はあるがそれの発揮の仕方がわかっていない"状態への移行を論ずる論考である。 (註2) 実際,AIでは,問題はコンピュータにインプットされるのであり,問題との対峙という局面を省略している。 3.6 問題の受容 問題の受容は,心の機制によってそれの内的表象がつくられることである。この内的表象が,問題解決主体にとっての問題である")。 特に,問題解決機制論では二種類の"問題"──問題解決主体から独立な存在としての"問題"と問題解決主体に依存する"問題"──が,それぞれ実体的存在として措定されていることになる。 この二種類の"問題"の措定は,二種類の"意味"概念の導入を必要とさせる。即ち,問題解決主体から独立な存在としての問題を"問題"として身分づける"意味"が先ず必要であり,これには字義的意味をあてる。また,問題を問題解決主体に依存するものとする"意味"が必要であり,これには文脈依存的意味をあてる。 内的表象化としての問題の受容,二種類の問題,および二種類の意味,これらの論点は合理主義的オリエンテーションの一般的論点の適用に他ならない。(それは,例えば,合理主義的オリエンテーション下のコミュニケーション理論における"メッセージの受容"の論点と同型である。)

information about what is desired, under what conditions, by means of what tools and operations, starting with what initial imformation, and with access to what resources. The problem solver has an interpretation of this information ── exactly that interpretation which lets us label some part of it as goal, another part as side conditions, and so on. Consequently, if we probvide a representation for this information (in symbol structures), and assume that the interpretation of these structures is implicit in the program of the problem solving IPS, then we have defined a problem.(Newell and Simon,1972,p.73) [Problem comprehension] involves at least two sub-stages: translation and internalization. Translation involves interpretation of the information the problem provides into terms which have meaning for the student. Internalization requires that the problem solver sort out the relevant information and determine how this information interrelates. Most importantly, this stage results in the formation of some sort of internal representation of the problem within the problem solver.This representation ... furnishes the student with a means of establishing goals or priorities for working on the problem. ... The accuracy of the problem solver's internal representation may increase as progress is made toward a solution. (Lester,1978,p.79) 3.7 自動機械の上の事態としての問題解決 問題解決は,自動機械の一連の動作として解釈される。 《問題解決は人に依存する》という事実は,自動機械の

(2) 初期状態 3.8 問題解決の機制 "問題解決"としての自動機械の動作は,表象に対する表象の作用──問題の逐次的変形の各ステップに対応する表象Rに対しての,或る表象Sの選択,そしてRへのSの適用──である。表象に作用する表象(手続き的表象)は,"方法 method"(Newell and Simon,1972) あるいは"ストラティジー"と呼ばれる。 こうして,問題解決は内的表象の上の出来事──問題の逐次的変形の各ステップに対応する表象に,ストラティジーが手続き的に関わっていく過程──として了解される。 3.9 問題空間の探索 Newell and Simon,1972 にほぼ倣って,"問題解決"をつぎのように定式化する")。 先ず,"タスク環境"の概念を導入する。 つぎに,問題の受容として,タスク環境の内的表象が問題解決主体の中につくられるとする。この内的表象は,既に内的表象として存在している"方法(ストラティジー)"とともに,"問題空間 problem space"を構成する。問題空間は,謂わば問題解決プログラムのデータ部を構成する。 最後に,問題解決を,

(2) 目標の到達に向けての,ストラティジーの選択肢の探索(問題空間での探索) (3) 目標に到達する探索経路のうち最も適切なものの選択 こうして,問題解決は"問題空間の中の探索"として表現されるものになる。即ち,《ストラティジーの選択とそれの適用》により,所与の問題に対応する表象が次第に解に対応する表象に変化していく,という図式である"2)。 この探索は,ストラティジーが適用される表象をノードとし,ストラティジーを選択肢とする木 tree で表現される。 (註1) Newell and Simon,1972 における"問題解決"の定式化では,実際多くのことが曖昧なままにされている。その定式化は,論理的というよりは,むしろ非常に感覚的である。 (註2) この発想の元には,H.A.Simon の意志決定理論がある:

3.10 ストラティジーの所有 問題解決論のオリエンテーションでは,問題解決主体は自分が所有しているストラティジーを使って問題を解く"1)。 特に,"ストラティジーの所有"が問題解決の内的な要件であることになる。そして,"わからない/できない"は,自己の内なる欠落"のことばで説明されところのものとなる"2)。 "ストラティジーの所有"の概念は,"ストラティジーの所有形態","ストラティジーの発動形態"の問題をもたらす。 合理主義的(特に,表象主義的)オリエンテーションに従うならば,ストラティジーは内的な命題として所有される。即ち,ストラティジーを言い表わす命題/命令文が,その意味を保存しつつ形のみを変えて──即ち,翻訳として──内的に所有される。そして,命題的態度 propositional attitude (Cf. Fordor,1978b) としてストラティジーが発動していることになる。

(註2) 問題解決論のオリエンテーションでは,問題解決は問題空間の探索であり,よって解決不能とは探索に失敗することである。それは,ある障害に全ての手続き(ストラティジー)が躓くということである。したがって,解決不能は,その障害に躓かずに済むストラティジーの欠如として説明されるものになる。 3.11 スキーマ 問題解決主体に対する自動機械の解釈の下では,"スキーマ"は"データ構造"に対応する。(一方,表象はデータに対応する。)"スキーマ"とは,内的表象(特に,ストラティジー)の構造を指す概念である──この意味において,それは問題空間を規定する因子になっている。 3.12 ストラティジー発動の機制の説明不能 "ストラティジーの選択"の概念は,"ストラティジー発動の機制"の問題を引き起こす。 "メタ認知"の概念が,ストラティジーに対する"driving force"として導入されることがある。しかしこれは,解決をもたらすものにはならない。実際,メタ認知の実体はメタ表象であるとされるので,"メタ認知"の導入は新たなストラティジーの導入に他ならず,したがってそれは単に"ストラティジー発動"の無限後退の問題をもたらすだけである。 3.13 問題解決機制論の基底 ストラティジー発動の無限後退の論難を免れるためには,ストラティジー発動を表象の作用とは異なる事態として考えなければならない。 即ち,ストラティジー発動は,自動機械のプログラムとして理解されねばならない。(Newell and Simon の Logical Theorist はこの設計を採用している。)──探索の現実的解決法としての"heuristics"は,このレベルの機制であると見なされる。(現実には,厳密な身分づけの下でこの用語が使われているわけではない")。) "プログラム"の概念を問題解決主体に移すならば,それは"傾向性"になる。結局,問題解決機制論は,その根底に"傾向性"というブラックボックスを用意しなければならない。この事態は,"説明はどこかで終わらなければならない"という Wittgenstein のことばと符合する。

(Winograd and Flores,1986,pp.33,34) 3.14 "メタ認知"の矛盾 "メタ認知"のアイデアは表象主義に即いている。そして表象主義の意義は,機制の記述レベルの実現にある。しかし,"メタ認知"の機制の説明は,有限システムの立場と矛盾することになり,破綻する。 実際,"メタ認知"の概念からは,"メタの無限累積"──これは,"デカルトの小人"の無限後退と同型──が自ずと導かれる")。このことは,論理レベルに関する内容ということでは,少しも困ったことではないが,認知レベルに関する内容ということでは,論点になる。 即ち,合理主義の機械論的オリエンテーションに従うなら,"メタの無限累積"には,認知モジュールを無限に入れ篭にするアーキテクチャが対応しなければならない。このアーキテクチャは,合理主義的な認識(直観)──"認知システム"は有限システムであるという認識(直観)──と相容れない。 表象の認知ユニットは,論理的に,一つか無限かである。そして,合理主義的オリエンテーションの下では,認知ユニットは一つでなければならない。 このように,"メタ認知"は表象主義の論理において破綻する。"メタ認知"を阻却するのにわれわれは,表象主義の外に出る必要はない。 "メタ認知"のアイデアは,〈言語〉の"タイプ理論"に対応して〈認知〉の"タイプ理論"をつくることにある。表象の論理レベルに直接対応させる形で認知レベルを導入する。"メタ表象"には,"メタ認知"が対応しなければならないというわけである。 しかし,これは錯誤である。この錯認により,理論は破綻している。 実際には,認知には一つのタイプしかない──メタ表象に対応する認知は"メタ認知"である必要はない──としなければならないのである。 もし"メタ認知"の語を導入しようとするなら,それはつぎのように使われるとしなければならない: (1) "メタ認知"の語を名詞あるいは動詞としては使わない;それはつねに"的"を付した形容詞として使う("メタ認知"ではなく"メタ認知的")。 (2) "メタ認知的X"は,"メタ表象に対する/関するX"と読む。 例えば,"メタ認知的知識 metacognitive knowledge"は,"メタ表象に関する知識"と読む"2)。 もっとも,このオリエンテーションは,"メタ認知"の主題の確立を意味しない。それは単に,"メタ認知"の主題の解消を意味する。 (註1) 一般に,"メタ"の概念は,メタの無限累積という事態を自然に導く。 (註2) 以下の言説を有意味なものとするには,ここで示した読み方をしなければならない: ... the monitoring of a wide variety of cognitive enterprises occurs through the actions of and interactions among four classes of phenomena: (a) metacognitive knowledge, (b) metacognitive experiences, (c) goals (or tasks), and (d) actions (or strategies). Metacognitive knowledge is that segment of your (a child's, an adult's) stored world knowledge that has to do with people as cognitive creatures and with their diverse cognitive tasks, goals, actions, and experiences. ... Metacognitive experiences are any conscious cognitive or affective experiences that accompany and pertain to any intellectual enterprise. ...(p.906) "Metacognition" refers to one's knowledge concerning one's own cognitive processes and products or anything related to them ... (Flavell,1976,pp.) Metacognitive experiences can have very important effects on cognitive goals or tasks, metacognitive knowledge, and cognitive actions or strategies. [They can] ... [1] lead you to establish new goals and to revise or abandon old ones. ... [2] affect your metacognitive knowledge base by adding to it, deleting from it, or revising it. ... [3] activate strategies aimed at either of two types of goals ── cognitive or metacognitive. (Flavell,1979,p.908) Cognitive strategies are invoked to make cognitive progress, matacognitive strategies to monitor it. (Flavell,1979,p.909) ... the monitoring of cognitive enterprises proceeds through the actions of and interactions among metacognitive knowledge, matacognitive experiences, goals/tasks, and actions/strategies. (Flavell,1979,p.909) Let us begin at the point where some self-imposed or externally imposed task and goal are established. ... your existing metacognitive knowledge concerning this class of goals leads to the conscious metacognitive experience that this goal will be difficult to achieve. That metacognitive experience, combined with additional metacognitive experience, causes you to select and use the cognitive strategy of asking questions of knowledgeable other people. Their answers to your questions trigger additional metacognitive experiences about how the endeavor [effort] is faring [turning out]. These experiences, again informed and guided by pertinent metacognitive knowledge, instigate the metacognitive strategies of surveying all that you have learned to see if it fits together into a coherent whole, if it seems plausible and consistent with your prior knowledge and expectations, and if it provides an avenue to the goal. This survey turns up difficulties on one or more of these points, with the consequent activation by metacognitive knowledge and experiences of the same or different cognitive and/or metacognitive strategies, and so the interplay continues until the enterprise comes to an end. (Flavell,1979,p.909) 3.15 "メタ認知"の構造 以下では,"メタ認知"の構造──即ち,"メタ認知"として錯認される認知の構造──を,明らかにする。 この目的のために,われわれは形式的記述──形式言語の文法の記述に類似した記述──を用いることにする。この形式的記述を用いることで,"メタ認知"の構造の議論を紛れのないものにすることができる。 3.15.1 行為語,モニタ語,志向語 先ず,語に関する"行為語","モニタ語","志向語"の三つのカテゴリーを導入する。 二つの有限集合A,M,Iを定める。それぞれ,行為を表現する動詞の集合,モニタ行為を表現する動詞の集合,志向を表現する動詞の集合である。 モニタ語を,つぎのように(再帰的に)定義する: (1) Mの要素はモニタ語である; (2) 二つのモニタ語x,yに対し,x"y,x"yはモニタ語である。 (3) (1)と(2)によって生成される記号列のみがモニタ語である。 また,これと全く同型に,志向語を定義する。 そして,行為語をつぎのように(再帰的に)定義する: (1) Aの要素は行為語である; (2) モニタ語は行為語である; (2) 志向語は行為語である; (3) 二つの行為語x,yに対し,x"y,x"yは行為語である。 (4) 行為語xとモニタ語yに対し,x←yは行為語である。 (5) 行為語xと志向語yに対し,x<yは行為語である。 (6) (1)-(5)によって生成される記号列のみが行為語である。 ここで,x"y,x"y,x←y,x<yを,それぞれ"xかつy","xまたはy","x自分をy","xことをy"と読む")。 例: A={歌う,踊る},M={観察する,点検する},I={好む,欲する} からは,つぎのような行為語が生成される: 歌う 観察する 好む 歌うかつ踊る 観察するかつ点検する 好むかつ欲する 歌うかつ観察する 歌うかつ好む 観察するかつ好む 歌う自分を観察する 歌うことを好む 踊るかつ(歌う自分を観察する) 踊るかつ(歌うことを好む) (歌う自分を観察する)自分を点検する (歌う自分を観察する)ことを好む (歌うことを好む)自分を点検する (歌うことを好む)ことを欲する ・・・・ 3.15.2 志向性(命題的態度) ここで,合理主義的オリエンテーションに従い,認知を志向性(命題的態度)と同一視する。 志向性は,一般に,命題(陳述文)pと志向語Iに対する記号列I(p) で表わされる──但し, "pということ(事態)をI" と読む。 ここでは,pを,行為語aに対する "わたしはa者である" という形の命題に限定し, I(わたしはa者である) をI(a) と略記する。このときI(a) の読みである "(わたしはa者である)ということをI" は,結局 "aことをI" である。 例: 行為語"歌う"と志向語"好む"から,志向性 "(わたしは歌う者である)ということを好む" ──通常の言い回しでは, "歌うことを好む" 3.15.3 "メタ認知"の構造 以上の準備の下に,"メタ認知"──"メタ認知"として錯認される認知──はつぎのように定式化される。 即ち,行為語a,モニタ語m,志向語I,Jに対し,志向性 J((a<I)←m) としての認知Aは,志向性 I(a) としての認知Bの"メタ認知"と呼ばれる(錯認される)。 例: 行為語"歌う",モニタ語"観察する",志向語"好む","欲する"に対し,志向性: "(歌うことを好む自分)を観察することを欲する" としての認知Aは,志向性: "歌うことを好む" としての認知Bの"メタ認知"と呼ばれる(錯認される)。 3.15.4 "メタ認知"錯認の構造 認知J((a<I)←m) に対する"認知I(a) のメタ認知"の読みは,J((a<I)←m) をあたかも J(I(a)) のように受け取ってしまう錯認による。 4 問題解決能力論 4.1 "good problem-solver" の概念規定 4.1.1 含意の特定による概念規定 数学的問題解決論では,"good problem-solver"の概念規定が,含意を特定する形式でなされている")。 一般に,概念規定の生活実践的な形式は,定義ではなく,含意の特定によるものである。定義の形式の概念規定ができるのは,規範学の場合に限る。 含意の特定による概念規定は,概念の確定にはならない。この形式の概念規定は,将来の含意特定に対して開いている。これが,日常語が更新される仕方である。 (註) 即ち, (1) "good problem-solver"["poor problem-solver"] と見なす対象を観察し, (2) その対象の傾向性("属性")を或る言い回しにおいて導出し,そして (3) その言い回しを,"good problem-solver"["poor problem-solver"] の含意と定める。 4.1.2 "good problem-solver" の概念規定の目的 含意の特定による概念規定の本来の目的は,概念的説明を可能にすることである"1)。 しかし,問題解決論における"good problem-solver"の概念規定の目的は,問題解決能力を構成する要素のリストをつくり, "彼/彼女が good problem-solver でないのは, good problem-solver の要素である・・・・が欠けているからだ" という形の説明を可能にすることである。実際,欠落の対象化の上に欠落補綴のための指導としての問題解決指導が立つ"2)。 (註1) 含意の特定による概念規定は,概念の確定にはならないが,概念的説明を可能にする。即ち,YがXの含意であるとき, "それがYであるのは,それがXであるからだ" という説明が可能になるが,これが"概念的説明"と呼ばれるものである。 (註2) What are the specific characteristics of successful problem solvers? ... What prerequisite skills, abilities, etc. and what level of cognitive development must a student have in order to solve a particular class of problems? (Lester,1978,p.59) 4.1.3 "good problem-solver" の概念規定の実際 "good problem-solver" の概念規定は,ストラティジーおよびメタ認知を特定する営みにおいて実現されている。実際,ストラティジー/メタ認知の表現として導入される言い回し"Xをする"は, "good problem-solver はXをすることができる" という言い回しを妥当とするものであり,"good problem-solver"の含意になることで逆に"good problem-solver"の概念を規定するものになっている。 以下は,Flavell,1979,Lester,1978,Lester,1983,Garofalo and Lester,1985 の中で挙げられているストラティジー,メタ認知を,(中には,表現を変えつつ)ピックアップしたものであるが,これらは確かに,"good problem solver"/"poor problem solver"の含意として,逆に"good problem solver"/"poor problem solver"の概念を規定するものになっている: having a good mathematical background, having a good variety of experience with problems, perseverance, tolerance for ambiguity, positive attitudes, resistence to distraction, field independence divergent thinking. distinguishing relevant from irrelevant information, quickly and accurately seeing the mathematical structure of a problem, generalizing across a wide range of similar problems remembering a problem's formal structure for a long time knowing that most problems can be solved in more than one way knowing that many interesting problems take more than 1 or 2 minutes to solve). knowing that some problems may have more than one correct answer whereas others may have no answer, due to insufficient information. realizing the importance of organizing information willingness to engage in problem solving. doing good mathematical achievement good visual perception viewing problem solving as a multifacted complex of processes knowing that many problems allow multiple solution methods choosing approaches to problems, avoiding blind alleys allocating problem-solving resources having good skill in organizing information good reading ability good spatial ability good verbal and general reasoning ability good spatial ability, makeing a good combination of the followings: making a table, drawing a diagram, organizing a list of information gessing and testing trial-and-error looking for a pattern looking for an inductive argument if there is an integer parameter, systematizing inference using and/or developping visual aids simplifying the problem using and/or developping simpler problems trying a similar approach with fewer variables establishing subgoals. recalling and using previous experiences arguing by contradiction or contrapositive, identifying goals and subgoals global planning local planning (to implement global plans) performing local actions monitoring to progress of local and global plans trade-off decisions (e.g., speed vs. accuracy, degree of elegance) having not only adequate knowledge but also sufficient awareness and control of that knowledge. monitoring one's task understanding and regulate one's strategy usage. selecting strategies to aid in understanding the nature of a task or problem, planning courses of action, selecting appropriate strategies to carry out plans, monitoring execution activities while implementing strategies evaluating the outcomes of strategies and plans revising or abandoning nonproductive strategies and plans self-questioning and self-answering in the sense of monitoring: 1. problem comprehension stage -- What are the relevant and irrelevant data involved in the problem? Do I understand the relationships among the information given? Do I understand the meaning of all the terms that are involved? 2. goal analysis stage -- Are there any subgoals which may help me achieve the goal? Can there subgoals be ordered? Is my ordering of subgoals correct? Have I correctly identified the conditions operating in the problem? 3. plan development stage -- Is there more than one way to do this problem? Is there a best way? Have I ever solved a problem like this one before? Will the plan lead to the goal or a subgoal? 4. plan implementation stage -- Am I using this strategy correctly? Is the ordering of the steps in my plan appropriate, or could I have used a different ordering? 5. solution evaluation stage -- Is my solution generalizable? Does my solution satisfy all the conditions of the problem? What have I learned that will help me solve other problems? Evaluation of orientation and organization: 1. Adequacy of representation 2. Adequacy of roganizational decisions 3. Consistency of local plans with global plans 4. Consistency of global plans with goals Evaluation of execution: 1. Adequacy of performance of actions 2. Consistency of actions with plans 3. Consistency of local results with plans and problem conditions 4. Consistency of final results with problem conditions understanding what such variations as abundant or meager, familiar or unfamiliar, redundant or densely packed, well or poorly organized, delivered in this manner or at that pace, interesting or dull, trustworthy or untrustworthy imply for how the cognitive enterprise should best be managed and how successfully its goal is likely to be achieved knowing what strategies are likely to be effective in achieving what subgoals and goals in what sorts of cognitive undertakings. escaping from the followings: useing only a random trial-and-error strategy in solving process problems, if they are unable to decide on a computation to perform coordinating simultaneously the multiple conditions present in a problem ignoring one or more conditions as they work on a problem recognizing the need to coordinate multiple conditions but not being able to do so. forming problem representations based on syntactic interpretations only. crunching numbers failing to gain "good" understanding of the problem statement before beginning to try to solve the problem 4.2 "問題解決能力"の措定 4.2.1 数学的問題解決論のジレンマ 数学的問題解決論は,最初から無理なスタンスを余儀なくされている。即ち,認知科学内問題解決論が,問題解決機制論として,問題に対してストラティジーを論ずるというスタンスをとっている")のに対し,数学的問題解決論=問題解決能力形成論は,問題フリーでストラティジーを扱わねばならない。 さらに,問題解決機制論は coherence theory として自立するものであるが,数学的問題解決論はこの問題解決機制論の枠組みをそのまま継承しながら,しかも correspondence theory であろうとしている。 (註) Newell, Simon の GPS (General Problem Solver) にしても,文字通り"GPS"というわけではなく,与えられたゴールに到達する道筋を求める問題──しかも,高度にフォーマティングされた問題──を解くようになっている。 4.2.2 "問題解決能力"措定の不能 合理主義的オリエンテーションに従うときの"問題解決能力"に対する理解の仕方は,共時態的/因果法則的である"1)。特に,"欠落"と"充填"が"問題解決能力"に対する第一次的な理解形式である。 また,問題解決を規定しているものは,所有のストラティジーであるとされている。よって,問題解決能力の措定の仕方は,ただ一つであるように見える。即ち,"問題解決能力"を所有のストラティジーと同一視するというものである。 しかし,これではうまくいかない。実際,"問題解決能力"に対する上のような理解の仕方では,"問題解決能力の伸長"を捉えられなくなる。 即ち,この場合問題解決の伸長はこれまで持っていなかったストラティジーを新たに持たせることでなければならないが,問題解決論のもう一つのオリエンテーションに従うならば,ストラティジ−を増やすことは問題解決能力の伸長を必ずしも意味しないのである。 実際,問題解決はストラティジーの探索として遂行されることになっている。したがってストラティジーをむやみに増やすことは,問題空間を処置不可能なまでに膨らませてしまうことになるのである"2)。所有のストラティジーが多ければ多いほど問題解決能力が高いと見なしたいところであるが,ここで合理主義的オリエンテーションによる問題解決の独特の捉え方が,ネックになってくる。 このように,"問題解決能力"の措定の主題化において,われわれは二つのオリエンテーション──"量"と"探索"──の矛盾に突き当たる。この矛盾の意味するところは,問題解決機制論と"問題解決能力形成"の発想の両立不可能性である。この矛盾は数学的問題解決論にとって致命的なものである。 (註1) この理解形式が顕われている言い回しの例として: Even the most successful problem solvers have difficulty in identifying why they are successful, and even the best mathematics teachers are hard pressed to pinpoint what it is that causes their students to become good problem solvers.(Lester,1978,p.54) (註2) 従来,ストラティジーの列挙・分類(タクソノミー)をストラティジー論の一部として受容する傾向があるが,ここで述べた理由において,それは誤りである。"ストラティジーの列挙"の形で実際に行なわれていることは,"good problem-solver"の概念規定(§3.1)である。 4.3 問題解決能力機制論 4.3.1 内容フリーの機制の説明 "問題解決能力"論は,主題としては,《内容フリーの機制の説明》という一点において,認知科学内問題解決論=問題解決機制論から一歩前進するものになる。"問題解決能力"の機制を説明するとは,内容フリーの機制を説明(ボトムアップ的に説明)することである。 しかし,問題解決能力形成論としての数学的問題解決論は,この主題については,今のところ何の展開も示していない。──"展開"を言う以前に,"問題解決能力"の措定という出発点で躓いたまま起き上がれないでいるというのが現状である。 5 問題解決能力形成機制論 5.1 問題解決機制論の暗黙的破棄 "問題解決能力"とストラティジ−を同一視するという発想は,問題解決機制論と矛盾する(§4.2.2)。しかし,合理主義的(特に表象主義的)オリエンテーション下では,これの対案は考えられない。実際,表象を巡る因果的図式は,どれも似たり寄ったりのものになる。 したがって,問題解決能力形成論を展開しようとするためには,"矛盾を見ない"ことにしなければならない。ここに,認知科学内問題解決論の中心的論考であった問題解決機制論が,閑却(暗黙に破棄)されることになる。 5.2 問題解決能力形成の機制の説明不能 合理主義的オリエンテーションの下では,問題解決能力と所有ストラティジーの同一視により,問題解決能力の形成はストラティジーの形成と同一視される。 さらに,ストラティジーは手続き的な内的表象として理解される。したがって,問題解決能力形成機制論は,手続き的内的表象の形成の機制についての論考ということになる。 しかし,この機制の主題化は純粋に理論的なものである。即ち,主題は立つが,この主題にアプローチする術をわれわれは持たない。 合理主義的オリエンテーション下の"内部の視点"では,この不能は主題の難しさに帰せられる。"外部の視点"では,擬似問題ということで,この主題の解消がなされる。 6 問題解決能力形成実践論 6.1 経験的アプローチ 問題解決能力形成の実践論は,〈ストラティジー=手続き的内的表象〉形成の実践論ということになる(§5)。指導論としては,ストラティジー指導論になる。 しかし,問題解決能力形成の機制論が空白であることにより,この実践論(指導論)は,経験的アプローチによってつくられる他ない。確かに,"能力形成"を目的とする実践の特徴づけは,"ストラティジーの形成"ということで明確になっている。しかし,ストラティジー形成の方法については,ここまでの理論は何の示唆もできない")。 この点に関しての問題解決論者の認識を,ここではつぎのようなもの──トップダウンの考え方──であるとする: 《問題解決能力形成実践論の実践の中から問題解決能力形成機制論に属する知見の得られることが,期待される》 (註) Can problem solving be taught? .... If problem solving can be "taught", what type of experiences must enhance the development of this ability?(Lester,1978,p.59) 6.2 "ストラティジー指導"の発想経路 "ストラティジー指導"の発想は,合理主義的オリエンテーション下にあって初めて現出し得た。この発想の経路をここで改めて確認しておく。 合理主義的オリエンテーションは,問題解決を問題空間における探索として解釈させる。探索の選択肢は,手続き的表象としてのストラティジーである。ストラティジーが作用する表象は問題に依存する。しかし,ストラティジーは問題に依存しない。よって,"ストラティジー"の概念は"問題解決能力"の対象化を可能にする(ストラティジーに実体化される概念として)。──こうして,"問題フリーな問題解決能力"という途方もない内容の概念が,"ストラティジー"の概念から簡単に導かれてしまう。 さらに,ここで描かれた図式は,"問題解決能力の形成"を現実的なもののように見せる。何故なら,ストラティジーは,手続き的な表象とはいえ表象には違いない。さて,"表象"に対するわれわれのイメージは"知識"である。したがって,"ストラティジーの形成"は"知識の形成"のようにイメージされる。ところで"知識"の形成は現実的なものである。したがって,ストラティジーの形成も現実的である。結局,問題解決能力は形成できる。 6.3 ストラティジー形成の実践における採用仮説 問題解決能力形成機制論が白紙だからといって,ストラティジー形成が全くの白紙で実践されるわけではない。即ち,その実践には,それが拠って立つ仮説がなければならない。 このような仮説としては,差し当たりつぎの二つが考えられる: (a) ストラティジーは,それを言い表わす日常文に対応する内的表象として所有される (b) ストラティジーは,それのプロトタイプとなる行為の内的表象として所有される また,両方が採られる場合もあるとする。 (a),(b) は,現在"ストラティジー指導"と称されているものの観察から遡行して得られる。実際,ストラティジー指導では (A) ストラティジーを明示する") (B) ストラティジーを暗黙のままにする のいずれかであるが,現前の"ストラティジー指導"には両方がある。そして,実践 (A) には仮説 (a) が,実践 (B) には仮説 (b) が,それぞれ対応することになる。 しかし (b) は,本来,合理主義的オリエンテーションからは外れる。合理主義的オリエンテーションは法則定立的オリエンテーションであり,"行為の内的表象"では法則の定立が望めない。 そして,(b) が退けられるとき,(B) の形態の指導がストラティジー指導から退けられることになる。 (註) 即ち,学習者の前でストラティジーをストラティジーとして直接ことばに表わし,これを標語のごとく学習者の内に浸透させる。 6.4 内容フリーの機制の説明不能との関連 既に述べたように(§4.1),問題解決能力の内容フリーの機制は説明不能となっている。この限りで,ストラティジーを内容フリーな問題解決能力の理由と見なすのは臆見に過ぎない")。特に,ストラティジー指導の後に問題解決能力の実現が見られたとしても,それはストラティジー形成の証拠にはならない。結局,ストラティジー指導を評価することはできない。 以上の意味においても,ストラティジー指導は無根拠である。 (註) ... can problem solving strategies be taught which are generalizable to a class of problems? .... the question arises concerning the extent to which learning to solve various types of mathematical problems transfers to solving nonmathematical problems ...(Lester,1978,p.59) 6.5 "ストラティジー指導"の実際 "ストラティジー指導"研究については,ストラティジーの特定と"とにかく問題を解かせてみる"というところで終始しているのが,現状である"1)。 ストラティジーの特定では,問題解決機制論に従えば,ストラティジーのレパートリーをむやみに増やすことはできない。一見,不足するよりは多過ぎる方がましなように(特に,算数/数学科で扱うことになる手続き的知識はどれもストラティジーに加えてしまえばよいように)思われるが,問題空間の爆発的肥大という理由から,そうはならないのである"2)。しかし,本節のはじめに述べたように,われわれは問題解決機制論を暗黙に破棄して問題解決能力形成論に進んでいる。したがって,ストラティジーのリストアップに関しては,特に制約はない。 (註1) The single most effective means for improving children's problem-solving performance is to have them try to solve a wide range of types of problems over a prolonged period of time without specific instructional intervention. (Lester,1983,p.241) (註2) 問題解決機制論を優先するときは,問題解決能力は, (1) 少数のストラティジーと (2) 生成的過程 の対で考える他ない。特に,ストラティジーのリストアップ作業は,(1) に対応して,ストラティジーの候補絞りでなければならない。 6.6 メタ認知の形成 既に述べたように,メタ認知の実体は表象ではあり得ない。したがって,メタ認知の形成のための指導をストラティジー指導と同類に考えることはできない。(現実には,ある種のストラティジー指導を"メタ認知形成のための指導"としている")。しかし,理論的に,それはあり得ないことである。)そしてこの意味での"メタ認知の形成"は,アプローチ不能な主題であるか,あるいは擬似問題であるかである。 (註) to stress specific mathematical problem-solving heuristics and managerial strategies that are useful in mathematical problem-solving. (Lester,1983,p.253) Metacognition instruction typically emphasizes having students discuss and think about the processes they use to solve problems in an effort to make them view problem solving as a multifacted complex of processes and to make them aware that many problems allow multiple solution methods. (Lester,1983,p.253) strategic behaviors take time to master ... novices need to develop the monitoring and assessing skills required to use them efficiently.(Garofalo and Lester,1985,p.166) ... the failure of most efforts to improve students' problem-solving performance is due in large part to the fact that instruction has overemphasized the development of heuristic skills and has virtually ignored the managerial skills necessary to regulate one's activity. ... much more attention should be paid to these aspects of using algorithms, strategies, and heuristics in instruction. (Garofalo and Lester,1985,p.173) ... children were encouraged to become self-conscious about their strategies and objectives. (Flavell,1976,p.235) |